C Surnames - Live Oak County Oral History Collection

Chapa Family Victoriano Chapa, 1812-1901 Prisciliano Chapa, 1840-1919 The Longhorns. 1985, University of Texas Press (3rd edition). Austin. 333-339. J. Frank Dobie, Author "Victoriano and Prisciliano Chapa, circa 1831-1919" The History of the People of Live Oak County. 1982. 239. Thelma Pugh Lindholm, Reporting

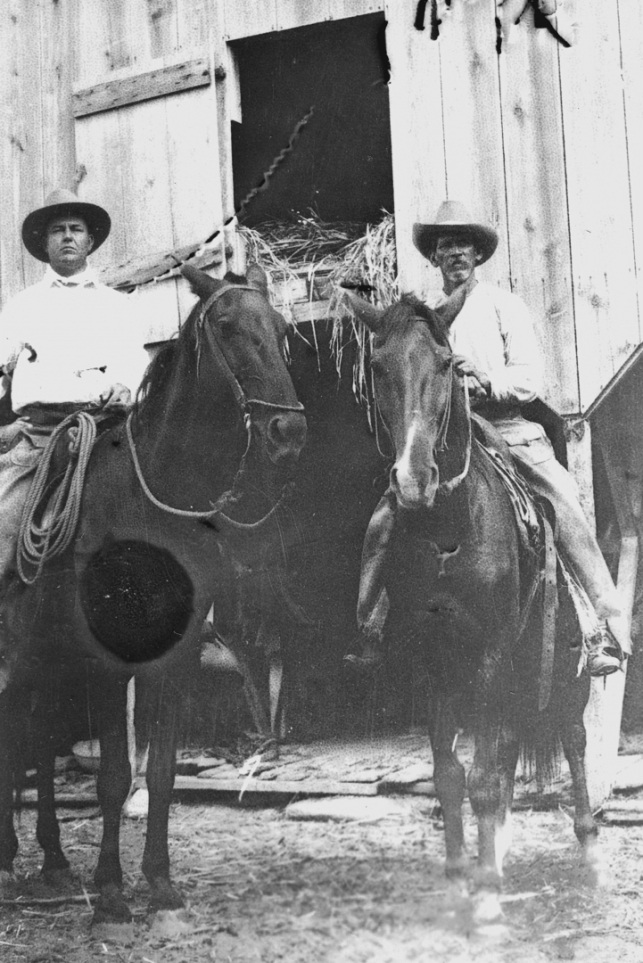

J. Frank Dobie and Don Victoriano Chapa - Photo from James Michener Center for Writers, University of Texas, Austin, Texas.Archive rendition by Richard Hudson preserved original age flaw.

According to folklorist, J. Frank Dobie, Victoriano Chappa was an amazing mix of vernacular Mexican tradition and later refinement. When he was 15, Victoriano and a friend were captured by Comanches and held for almost five years. While in captivity, the boys learned to live on raw horse meat and raw beef. They could go days without water, managing on prickly pear for fluid.

"Finally, they were camped near San Antonio, which Indians' amicably called their 'rancho'. Young men by then, Victoriano and his friend escaped while Comanches were hunting buffalo. Not stopping until at least a day and a half ahead of their trackers, some of the best in the world, they stopped at a little 'jacal' (native hut made of mud and sticks). The woman who lived there prepared corn for them, hid them beneath blankets and rawhides when the Indians caught up and refused to let the Indians have them. Lucky for her, Victoriano, and his friend, soldiers came near by, and the small band of Indians left rather than be rousted by the army."

Victoriano, resourceful and enterprising, became honorable Don Victoriano and owned tremendous holdings including horses, cattle, and land in what is now Live Oak County, Texas. After Victoriano's passing, the son, Don Prisciliano, willed half of his estate to the granddaughter of the woman who sheltered Victoriano from the Comanches.

The History of the People of Live Oak County, 1982. 239. Thelma Pugh Lindholm, Reporting

The Thomas and Margaret Pugh family, neighbors of Don Victorio and Don Prisciliano Chapa, raised five generations in this second home on the east bank of the Nueces River. Pugh's first house was a log home later used a guest house for overnight visitors like the Chapas.

Chapa's purchased 10,000 acres of land in Live Oak County around 1876 and afterward. The Pugh's land came from a Mexican grant and is now a Texas registered 150 year old farm. The Pugh's lived on their land for more than 40 years before the Chapa's made Live Oak County their home. Sixth and seventh generation Pugh's (2012) standing in front of the house are: (Back row left to right) Bill Pugh and Jim James. (Front row l to r) Kathy (Pugh) Howard, Theresa (Henning Pugh) Huebner, and Margaret (Pugh) James. Photo by Richard Hudson.

According to Thelma Pugh Lindholm, William Pugh, son of Thomas and Margaret, and his wife Ellen Maloy Pugh had six children. Their youngest was Charles Augustus Pugh, who was only two years old when his father died. Below is the story of a lifelong family bond.

"The friendship between the Pughs and Victoriano Chapa started long before Willam's death. Chapa had a large ranch in the Ramirena area. Chapa, soon after his friend's death, crossed the Nueces River at the Shannon Crossing, on horseback, bringing with him a nursemaid and an extra horse carrying saddle bags. They were guests at the Pugh home. The reeal reason for the trip? Chapa wanted to adopt Charles, stating he would will Charles the same ranch acreage as each of his own boys were getting. Ellen didn't say 'No,' she just asked him to give her more time. Charles stayed a Pugh and lived on the original home place."

In future writing, Lindholm, says that Victoriano and Prisciliano continued making the trip to the Pughs to be of help to Ellen and her children in any way possible. When Victoriano died, Prisciliano continued the connection even swimming the river when necessary.

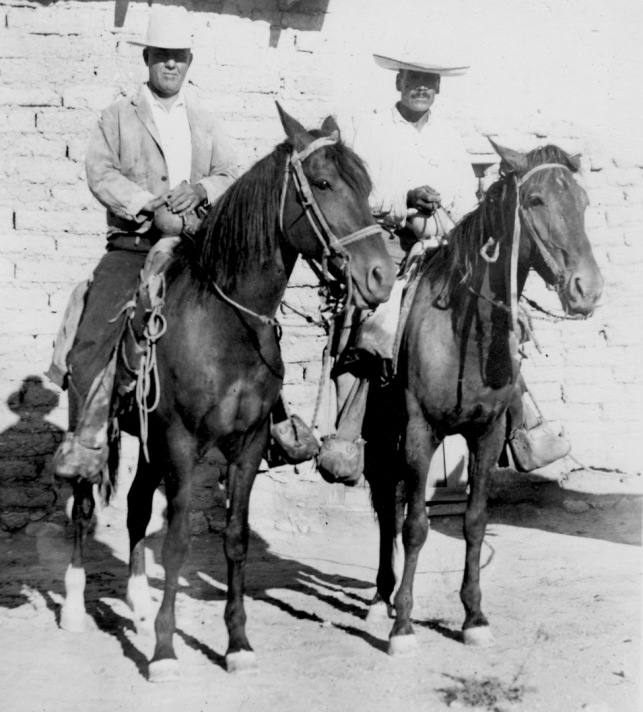

J. Frank Dobie and Don Prisciliano Chapa Photo from James Michener Center for Writers, University of Texas, Austin, Texas. Archive rendition by Richard Hudson.

Dobie's account of the Chapas brings together Victoriano's disparate early Mexican life and Indian captivity through Spanish, Mexican, and other European cultures which continue to shape life in Live Oak County and South Texas. Most ranchers in the area are fluent in Spanish, especially the Tex-Mex version, often switching back and forth to English in mid-stream conversation no matter what their native language. Some of Dobie's Spanish terms below are translated for the reader's benefit.

The land between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers was unsettled and wild before Texas independence and for some time afterward. Wild horses (mustangs) and cattle roamed unfenced prairie land and were free for industrious men and an occassional woman to round them up and lead them to a rancho, farm, or market. Dobie says:

"Don Victoriano used to tell how some lancers scouting between the Rio Grande and the Nueces caught him with a bunch of captured mustangs and made him bring them to Santa Anna's army, on its way to the Alamo."

"During the Civil War they [Victoriano and Prisciliano] made real money hauling cotton in ox carts from the interior of Texas to the Rio Grande - the only escape from the Federal blockade that the Confederacy had."

"There were prairies on it [the land Chapas acquired after coming over from Mustang Island with the Lynes] then, though ramaderos [sheltering areas] of dense brush and montes [small hills] of chaparral [small trees and brush] bordered and cut into the openings. In time they fenced it all. The Chapas raised Spanish horses and Longhorn cattle. They were quiet men, almost timid, quaintly honest in the way of simple people, and loyal to their own ways, people of the land."

"At the ranch house, on a hollow that makes the upper drainage of Ramirena Creek, they built a big tank. Don Victoriano laid off plots of ground for peon Mexicans, who carried the dirt out in rawhide bags, building a dam that holds to this day [1941]. To strengthen it against the rush of waters he butchered a heifer and mixed the blood into the earth at the center of the dam and at each end. This was the only permanent watering of any value on the whole ten thousand acres."

"Don Victoriano was the last ranchero in a big scope of country to use a cowhide for a table. squatting by it on the floor to eat. However, he was converted to table and chairs long before he died."

For the full story, read The Longhorns, J. Frank Dobie, any version. Above references are Third University of Texas Press Printing, 1985. 333-339.