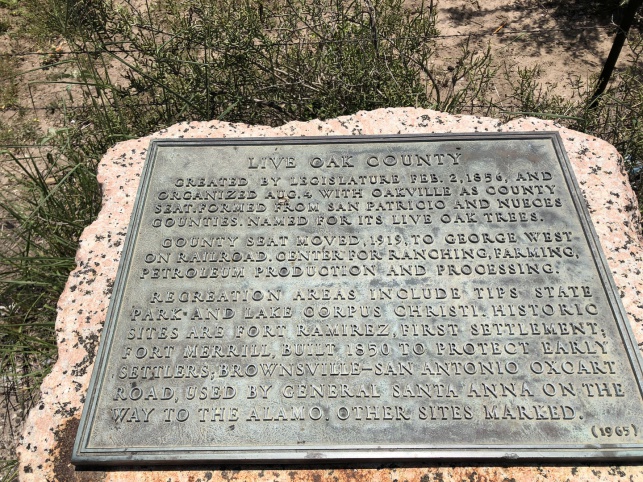

Live Oak County 1936 Texas Centennial Marker

In 1965, the Texas Historical Commission (THC) began a Texas Historical Marker Program, and history minded people in Live Oak County formed the The Live Oak County Historical Commission. They became vigorous about keeping the History of Live Oak County Alive. This was one of the first marker plaques the LOCHC placed on top of the above Centennial Marker through the auspices of the THC. Photo courtesy Richard Hudson.

County Historical Commissions did not exist in 1936.

Live Oak County Judge: Honorable C.B. Beard

Date Unveiled: 1936

1936 Texas Centennial Marker Text

Live Oak County

CREATED BY LEGISLATURE FEB. 2, 1856, AND ORGANIZED AUGUST 4 WITH OAKVILLE AS COUNTY SEAT. FORMED FROM SAN PATRICIO AND NUECES COUNTIES. NAMED FOR ITS LIVE OAK TREES.

COUNTY SEAT MOVED, 1919, TO GEORGE WEST ON RAILRAOD. CENTER FOR RANCHING, FARMING, PETROLEUM PRODUCTION AND PROCESSING.

RECREATION AREAS INCLUDE TIPS STATE PARK AND LAKE CORPUS CHRISTI. HISTORIC SITES ARE FORT RAMIREZ, FIRST SETTLEMENT; FORT MERRILL, BUILT 1850 TO PROTECT EARLY SETTLERS; BROWNSVILLE-SAN ANTONIO OXCART ROAD, USED BY GENERAL SANTA ANNA ON THE WAY TO THE ALAMO. OTHER SITES MARKED. (1936) Marker is property of State of Texas.

Live Oak County History Excerpts from various sources

APPLICATION NARRATIVES FOR CENTENNIAL MARKERS IN 1936 were not recorded. The following is presented for viewer information:

Live Oak County History

Prehistoric Times

Evidence of early grasslands and prehistoric animals have been found by archeologist, Jim Warren. A wooly mammoth skeleton found by Patrick Burns on his ranch and carefully recovered by Warren can be seen in the Armantrout Museum just outside George West.

Rudi Harst of San Antonio, accompanied by Buffalo Thunder del Toro, performed a "Prayer of the Four Directions" and other Native American music throughout the Loma Sandia program at the marker's unveiling. Photo courtesy Brett Walker.

LOMA SANDIA. Loma Sandia (41LK28), a prehistoric campsite and cemetery, is located in Live Oak County on a sandy knoll along a small tributary of the Frio River about three miles north of Three Rivers, Texas, and one mile south of U. S. Highway 281 and Interstate Highway 37. The name Loma Sandia, or “Watermelon Hill” in Spanish, derives from the fact that when the site was first discovered, the overlaying field was used for growing watermelons by local farmers.

The late Middle Archaic Indian campsite and cemetery covers approximately 15.15 acres; 46 percent of property is owned by the State of Texas and 54 percent privately owned. About 205 human skeletal remains discovered in a section of the cemetery were found closely interred on two separate levels. Strata analysis suggested that burials occurred from 850 to 440 B.C. A variety of tribes comprising about 200 bands and sharing a language dialect anthropologically described as Coahuiltecan ranged from San Antonio southward into Mexican Coahuila and Tamaulipas.

The cemetery predates by approximately 2,000 years the first European explorer and historian, Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, who traveled through South Texas and northern Mexico and later published an account of his adventure. The Coahuiltecan natives Cabeza de Vaca encountered made annual forays into the area to eat the succulent cacti tunas and pecans from trees along the Nueces River. Tubers, small creatures, earth substances, and occasional larger animals also contributed to their meager diet. Cabeza de Vaca's report of the area and native life was so descriptive that he is regarded as Texas' first ethnologist.

The Loma Sandia site advanced understanding of the ancient peoples of South Texas. Thomas R. Hester is director of the Center for Archaeological Research and an associate professor of Anthropology at the University of Texas in San Antonio. He states that when the site was excavated, earlier archeological findings in Live Oak County strongly implied that only single Indian graves existed, suggesting the existence of a nomadic culture with little or no societal or territorial boundaries.

Loma Sandia cemetery, however, documented a more communal, though itinerant culture, encamping periodically for religious and funeral rituals. This activity occurred over a period of several hundred years. Secondly, artifacts found with the burial remains show slowly developing tool sophistication over time. Other artifacts such as shells indicate trading patterns between coastal tribes, and certain materials and points used for hunting were traded among tribes farther west.

Excerpt taken from Handbook of Texas Online, Richard and Janis Hudson, "LOMA SANDIA," accessed September 20, 2016, http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/bbl18. Follow the link for additional information.

Spanish Settlement

Early in the 19th century the Spanish attempted colonization in this area, which was a part of two Spanish provinces, Texas and New Santander. Later, these became the Mexican States of Texas, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas. Many Spanish land grants were made on the west side of the Nueces River at this time, and about four incomplete grants within the area which now composes Live Oak County. All of these were in the southern part of the county, along the Nueces River and on the Ramirena and Lagarto Creeks.

In 1934, Dudley Dobie wrote, "one remaining evidence of the settlement on Ramirena Creek is the ruin of what was once a very substantial stone house, strongly built, no doubt, for defense against the Comanche and Lipan Indians who roamed at will over the country at that time. This old ruin is on the William Primm third league of land, south of the Ramirena Creek, and the building was still well preserved when the white people began to settle in that locality." According to Dobie, there is some record of this house that lends a clue to its history. The place was called "Ojo de Agua de Ramirena".

The ranch was abandoned in 1813 due to an influx of hostile Indians, when the owners, Don Jose Antonio Ramirez and Don Jose Victoriano Ramirez, lost their numerous flocks and herds and were forced to flee and leave their household effects. As told by the Mexicans, a strong force of Indians came and killed all of those who did not have time to get into the house and then the Indians left. The survivors likewise departed and never returned.

A Ramirez son made representation to a Mexican judge at Mier in 1827 that his father and uncle never voluntarily abandoned the ranch but were forced to flee by the hostile Indians, due to the withdrawal of the troops (called presidiales during the War of Mexican Independence from Spain) and the judge, finding that this was true, directed that a survey of the land be made. However, the land is held under a patent from the State of Texas, issued in 1848, and the record as to Ramirez serves only to show that it was the first settlement in Live Oak County. J. Frank Dobie wrote an excellent story about Fort Ramirez which is found in a chapter of his Coronado's Children.

Indians

After the failure of the Spaniards to colonize this area, the Indians roamed freely for a number of years. As with all westward migration in the United States, as the white settlers moved further inland, the Indians were pushed either over or up, and there was never an actual period of peaceful co-habitation. Early Texas legislative journals indicate that many areas in the early years and until about 1850 were subject to Indian raids on the white settlers and capture by the Indians of white women and children. One family story relates an "Indian scare" as late as 1890.

Several entries indicate that neutral peacemakers, among them Jim Shaw, a Delaware Indian, would undertake to locate captured children and negotiate their return for which the government then in existence would pay or reimburse the family. For this reason and the fact that this area was yet a wilderness, except for rare instances, there was not an intent migration to this area until McGloin and McMullen made application to the government of Mexico for their planned emigration of settlers from Ireland in 1828.

According to the records of Thelma Lindholm, perhaps the earliest introduction to the Indian came from N. Gusset's settlement, Gussettville. Mrs. Mary Gallagher, wife of Tom Gallagher, told that when they and the Sheeran family came from Ireland they settled as close neighbors in Gussettville on the Nueces River near where the Mikeska Bridge is today.

One moonlight night they sighted a big herd of cattle topping the hill in the vicinity of the present church building and when they neared the adobe huts they realized the cattle were driven by Indians. One of the younger Sheeran boys had a pony tied near their hut. An Indian stole up and cut the pony loose and took him off. The Sheeran boy loaded his gun and was determined to recapture his pony. Due to the fact that the odds were against the Sheerans and Gallaghers, the boy had to give up the idea of rescuing his pony. It was reported that about thirty of these Indians were later killed a short distance up the Nueces River.

The white people did not begin to settle permanently in the Live Oak County area until sometime after the Mexican War of 1846. However, the stage line was established in about 1846 through the country from San Antonio to Corpus Christi. The old road ran through or near the present site of the town of Oakville, and a stage stand was kept for awhile on the south side of Sulphur Creek. During the time it was maintained, a detachment of rangers and citizens from further east fought a battle with a band of Indians near where the old Oakville Courthouse stood. A number of Indians were killed and the rest were driven off.

According to the story about the fight, during the progress of the battle an Indian squaw, armed with a dangerous looking knife, chased one of the white men around a live oak tree and kept him on the run until she was killed. [This is known as The Last Indian Fight in Live Oak County and some say the last in Texas.]

Lindholm et.al. The History of the People of Live Oak County, Texas. George West: Self published by The Live Oak County Historical Commission.1982. 5-7.