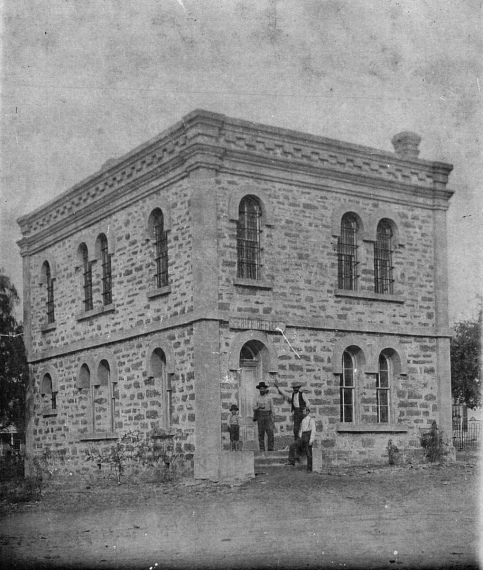

Live Oak County Jail-National Register of Historic Places

Original Live Oak County-Oakville Jail

Circa 1886-1919

White trims were painted on existing cornices, windows, and doors between this 1890s photo and time discussed in the narrative below.

At the time of the National Register narrative, this was the only building on Oakville Square. Before then, the entire jail had served as a home, but the last courthouse in Oakville had been removed.

Photo courtesy Margaret Custer.

At the time of the National Register's beginning application, the jail was vacant and endangered. now in the hands of its fourth owners, Albert and Mari Davila, the jail has been restored and renovated as a public venue. Many dwellings from historic Oakville itself and some interesting artifacts from the surrounding area have been restored, renovated, or reproduced through historic procedures for public use under the name of Historic Oakville Jailhouse and Guesthouses.

The narrative and bibliography below have been edited only because of changes required to make type readable. Secondly, since the original was written on mailable pages instead of an online stream, the demarcations required for each page were deleted in favor of continuous flow. Last, but not least, contextual page footnotes were not applicable in the streaming format. Yet, all bibliographical data is preserved. Application through the Texas Historical Commission was begun in 1990, presented for final approval to The National Register of Historic Places under the auspices of the United States Department of the Interior-National Park Sevice and granted on February 25, 2004. Pdf link of THC application: Live Oak County Jail Narrative.

Texas State Governor: Honorable Rick Perry

Texas Historical Commission Chairman: John L. Nau, III

Texas Historical Commission Executive Director: F. Lawrence Oaks

Texas Historical Commission National Register Coordinator: Gregory W. Smith

Live Oak County Judge: Honorable Jim Huff

Live Oak County Historical Commission Chair: Betty Lyne

Research and Narrative Preparation: Imogene Cooper with assistance from Bob Brinkman, Texas Historical Commission Marker Coordinator.

Date Approved: 1990

APPLICATION NARRATIVE and BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR OFFICIAL NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES STATUS:

(Oct. 1990)

United States Department of the Interior

National Park Service

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

Narrative and Bibliography

Live Oak County Jail

Oakville, Live Oak County, Texas

The Oakville Jail (1886-1887) is a small, two-story, nearly rectangular, Italianate-style building about eighty miles southeast of San Antonio, Texas. Located in the ghost town of Oakville, Texas, on Interstate 37, in Live Oak County, it is constructed of rough-hewn, random coursed, tawny-brown sandstone blocks that were hauled by ox-cart from a nearby quarry. It is crowned with a heavy built-up sandstone block cornice, which screens the low pitched, hipped, standing seam metal roof and guttering system. It has two corbelled chimneys. The stone facades of the first floor are separated from the second floor by a thick, white-stuccoed string course. Likewise, the building's corners have heavy, white-stuccoed pilasters. It once had triple hung windows that still employ heavy sandstone "eyebrow" lintels, stuccoed white and heavy sandstone sills. With formal symmetry these large windows were placed in pairs to coax cooler air to flow through the building during the oppressively hot South Texas summers. The building is only about thirty feet wide and forty feet long, but it was a state-of-the art jail at the time of its construction and the third and best detention facility to be built for the government of Live Oak County. It served as the county's jail from 1887-1919, while Oakville was the county seat for Live Oak County.

Architecturally, it is a rare style of jail, built from plans supplied by the Diebold Lock and Bolt Company of Ohio, complete with plans for strap metal cells and remote locking doors. The jail once shared the public square with the town's courthouse building and its public well, driven by a windmill. Now the square is vacant and the only remaining structure is the jail. But its presence still conveys a sense of strength, safety and

permanence as well as the town's hope for prosperity, rendered futile after the loss of the county seat and bypass by the nearby railroad line, which carried business to other, newer towns.

Exterior description

The Live Oak County Jail was constructed in the southeast corner of the town square. The narrow front facade of the jail faces east, and is constructed of rough-hewn, light brown sandstone blocks , which average 22 inches in thickness. The jail has two separate entrances, one for the sheriff and his visitors and one for the prisoners. The sheriffs front door faces the southeastern edge of the courthouse square and is part of the building's front facade. Here, a visitor would ascend up four cement steps to a narrow cement porch and then walk through a slightly recessed, arched and heavily hooded doorway. To the right of this front door is a pair of matched, double-hung and similarly hooded windows with heavy, deep sandstone sills . All of the building's window and door hoods are stone, but they are lightly stuccoed with cement and all are painted white. The second story fenestration is also tall and thin and symmetrically repeats the rhythm of the openings on the first floor.

Unfortunately, in the 1930s, all the sandstone sills and iron bars of the building's second floor windows were crudely removed so that all the building's original triple hung windows could be replaced with double hung

windows whose wide sashes could then be forced into the openings. Above the double hung windows, all the window arches were then in filled with plywood veneers, inside and out.

The southern facade is the building's most attractive side, and although a secondary façade, it forms the long side of the building and presents a handsome edge to the south side of the courthouse square. The south elevation has eight double hung windows, two as a matched pair in the center of the facade on the first floor, and two, as an identical matched pair immediately above on the second floor. Similar, but single windows flank these matched pairs on either side, except that the southwest window on the first floor is smaller for reasons of security and for the small room that it lights.

At the southwest corner of the building, on the west facade, the walls were made even thicker and they form a small ell facing west and forming the rear of the building, upstairs and downstairs, these thicker corner walls form the two small rooms that may once have been the jail's holding cells, Also found at the rear of the building. At the northwest corner, is the jail's above ground cylindrical metal cistern, which once received rainwater from a downspout that was connected to the roof.

With its conversion into a residence, the appearance of the jail's north facade was slightly altered with the addition of a simple, shed like porch placed in front of the back door at the northwest corner of the building.

This was the building's service entrance through which prisoners were taken, either to enter the long gone courthouse, once located just to the north and in the center of the courthouse square, for trial, or straight up to the cells on the second floor. Above this add-on porch, a window was crudely converted into a door, so that one could step out onto the roof of the porch. Despite the alterations, the north facade is still handsome and has six windows placed in a pattern similar to the south facade, with a window in the center on both the first and second floors, each flanked on the left with single windows, upstairs and down.

Interior description

Nineteenth century jails were usually constructed as two-story detention facilities. The first floor of the building served as living quarters and offices for the sheriff and his family, and the second floor contained the metal cells for the jail's prisoners. The sheriff was hired by the county for a salary of only $300.00 a year, but this included provision of housing in the jail, if the sheriff chose to use it. The first floor consists of five rooms and the stair hall. People on business with the sheriff entered through the front door on the east facade into a small reception room or foyer. On the right was a large room probably with a metal stove, as there is still a stovepipe hole in the ceiling and one of the building's two chimneys is immediately above. Perhaps this was the sheriff’s office. Straight ahead from the foyer is another larger room with a mantled, plastered fireplace at the west end; perhaps this was the family's living area. To the right of the living room is another room, perhaps a sleeping room. In the 1930s it was converted into a kitchen. All of the rooms had hardwood floors and high ceilings. Separate doors at the rear of the living room and kitchen lead to the back hallway and cast iron staircase that led up to the second floor jail facility. This back hall and staircase are also accessed by the back door as described above. And at the rear of this hall in the southwest corner was the tiny downstairs room with high windows, perhaps a downstairs holding cell. Currently it is plumbed as a bathroom.

The upstairs room once contained three metal cells. It was entered through a large door at the top of the staircase landing and had, at one time, a large, remote-locking metal door. The second floor rooms are partitioned from the staircase and landing with a thick wall that goes up through the attic to the roof. Two of the cells were for one prisoner each, and the third cell was a "double" cell with two cots. The upstairs floor also contained a small room at the top of the stairs and away from the common area. This room may have been for isolation of juvenile or female prisoners. When the jail was converted to a residence, a major interior alteration was the construction of a drop ceiling for the second floor and a partitioning of the space into an upstairs bathroom and three small bedrooms. While the building was a jail, the second floor was a completely open room and contained within it the three freestanding metal jail cells with their heavy strap metal bars, all surrounded by the

In 1919 Oakville lost the county seat to George West and went into a quick decline. Nearly the entire historic core of Oakville was bought by the Rosebrock family, including the 1856 courthouse and 1886 jail. The courthouse was a two-story stone building with three rooms on either side of a central hallway. By the time Oakville received a Texas Centennial historical marker at the courthouse square in 1936 nearly all other historic buildings had disappeared. The Rosebrocks lived in the jail building and demolished the courthouse in 1938. The loss of the courthouse caused some property disputes, as all land in Oakville and much of Live Oak County was surveyed and measured from the doorway of the courthouse. The jail remained vacant but still owned by the family before the current owner acquired the building in 1990. The historic jail remains a source of interest and inquiry by the general public, who often mistake the building for the historic courthouse.

In 2002-03, students from the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) documented the history and architecture of the Live Oak County Jail for HABS (Historic American Buildings Survey). In 2003 their documentation received the Charles Peterson Prize as the top student HABS documentation submittal nationwide. The HABS team included students Imogen Cooper, Yoshi Sharabani, Cheryl Davani, Julia Dunks, and Wanira Oliveira. UTSA assistant professor Sue Ann Pemberton-Haugh was the students' supervisor. Personal correspondence with Julia Dunks, graduate architectural student at the University of Texas at San Antonio, December 9, 2002. This description of the metal cells is based Ms. Dunks description of the Mills County Jail cells, which has been left intact in Goldthwaite, Texas. The Oakville jail cell configuration was almost certainly identical to that of Mills County.

The 1886-87 Live Oak County Jail in Oakville is immediately east of the Interstate 37 access road about eighty miles southeast of San Antonio, Texas. Because of its sturdy stone construction, the two-story jail building still stands on Oakville's otherwise empty town square. It is all that remains of a town that once served as the county seat of Live Oak County from its founding and the county's establishment in 1856 until 1919,when Oakville lost the county seat election to the nearby town of George West. From 1887 to 1919, the jail served as the county's third and most sophisticated detention facility while, concurrently, Oakville's population peaked to four hundred people. But the loss of the county seat caused a critical loss of the commerce and business that had always attended a county seat and the status it provided as a business address. The consequence was severe decline, despite the benefits provided by the then-modern jail. Oakville became a ghost town.

The Live Oak County Jail is nominated for listing in the National Register of Historic Pl aces under Criterion A, in the areas of Community Planning and Development and Law, and under Criterion C, in the area of Architecture, at the local level of significance.

As a reflection of Community Planning and Development, the jail was a tangible symbol of town aspirations to retain the county seat and to attract and retain the commercial activity and the prosperity associated with county seat status and a secure jail. The jail was also significant in the area of Law, for the jail was a symbol that the town had achieved civility and security both for citizens and incarcerated prisoners. The jail was a statement, literally in stone, that the lawless chaos occurring in Live Oak County after the Civil War and during the subsequent boom years of the cattle drives, as well as the careless, even life-threatening treatment of prisoners, had been permanently replaced with the law. Psychologically, the jail gave off an aura of security and stability. In the area of Architecture, the jail is important because it demonstrates an archetype of safe and humane incarceration for late 19th century as envisioned by reformers in the Texas legislature. Secondly, it is a rare surviving example of a style of jail construction offered as a "kit" by the Diebold Lock and Safe Company in Texas. Diebold built only eight jails in Texas and six of them used styles different from Oakville's. Oakville used style "S -47" and only one other jail, the Mills County Jail, uses this same plan.

Significance of the Property in Community Planning and Development

Community Planning

Live Oak County is found the south central heart of Texas; in an area known as "Brush Country." It is an arid land of brown sand that is covered with thick hedges of prickly pear cactus and acres of thorny mesquite tree s, good only for scrubby rangeland, if the cattle were tough enough, or for irrigated farming from deep wells, if the farmer was stubborn enough. Beg inning in 1856, Live Oak County was established, platted and chartered by the State of Texas and the town of Oakville was chosen as its county seat. The land for the town site, 640 acres, was a grant from Thomas Wilson, who also stipulated that there be separate squares marked out for public, graveyard, church and school uses.

Wilson lived on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, but he had holdings in the newly established county of Live Oak. In donating the land for the public squares, his hope was that the sale of lots around these squares would be brisk, as businesses tended to establish themselves adjacent to the courthouse square and then advertise themselves in weekly newspapers as "north of the courthouse square," or "on the south side of the main square."

Located in the town of Goldthwaite, in Mills County, Texas, the Goldthwaite jail is the "twin" of the Oakville Jail. National Register

Nomination for the Mills County Jail, <Accessed through the Texas Historical Commission's Online Atlas>

After liberation from Spanish and Mexican control, Texas communities were no long regulated by the Laws of the Indies, which stipulated that Spanish Colonial plazas must be designed as an open area around which were placed the church and the houses of government. The intent of the plaza function changed in the 19th century, when courthouses and jails were placed within the boundaries of the courthouse square signifying them as the center of government and civic activity. Thus, the Oakville jail was placed within the courthouse square as a symbol of law and justice for the community. Also, the sheriff’s front door, which was the main entrance to the jail, was oriented to face the street edging the square and thus affording him public respect as the chief law officer in the community.

Community Commercial Development

Even before 1856, an area near Oakville had been a place of commerce because it was the crossroads of ox-cart caravans and mule trains that crawled the muddy roads of Texas and were called, ironically, the Caminos Reales, or "King's Roads" of Spain. They ran from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico and Brownsville to San Antonio and from Laredo to Goliad. Near Oakville was a natural stone ford of the Nueces River called by the

Spanish, Puenta de la Piedra ("Rock Bridge") and so, after the sometimes dangerous and exhausting fording of the swift Nueces River; the town became a favorite resting place for the slow, slow ox-trains.

With the end of the Civil War, several enterprising Texans realized that real money could be made by rounding up the thousands of wild, surly, Spanish cows, called Longhorns that overran the brush country, branding them with a special, registered brand, and then herding and driving them north to towns like Abilene, Kansas, for shipment to the growing beef market on the East Coast. During the late 1870s, when the enormous cattle drives to Abilene were assembled and the free ranging and very wild Longhorn cattle were driven north up the Chisholm Trail, many cattlemen made handsome profits. Unbranded cattle were considered free for the taking if a cattleman could catch them, and they were called "mavericks."

The unbranded cows were called "mavericks" after a certain family in San Antonio, who it is said, never bothered to brand their cows, so they were called "Maverick's cows."

Most cowboys were literally that [mavericks], teenagers and young men in their early twenties. Charles Siringo started at age fifteen, and called himself a "stoved in" cowboy by age 26. None but the young could survive and endure the months of riding, herding, branding, camping out, and management of frequent stampede. All this work provided a monthly credit of about $15.00 to $40.00, plus a share of the profits, if any, at the end of the trail. (Siringo, A Texas Cowboy, p. 210.)

In this arid land, cattle ranching regularly failed too, due to the cyclical climate of drought and flood west of the fabled 98th meridian. T.R. Fehrenbach notes in his history, Lone Star State, that west of this meridian there is never enough rain for dry farming, only enough to grow the buffalo grass, a growth of eons. The droughts continue and are, even now, emptying out the farmlands as the grass returns.

Oakville became a small boomtown for the kind of trade that ranching activities needed. As the county seat, the courthouse was the place to record those special brands that the various ranchers burned into the hides of unclaimed Longhorns. The courthouse also kept records of the various ranchers' land claims as land titles.

Since frontier Texas was completely unfenced, the cattle mingled together over many square miles. When a rancher decided to drive a herd north, he and his crews of cowboys had to first search the brush for his branded cows, separate them out as his own, brand as many mavericks as could be found, and then plan the cattle drive. The drive north required special supplies from town; ranchers needed clothing from dry goods stores, saddles from tack shops, blacksmith services, groceries for weeks of camping out, as well as title companies and attorney services to wrangle over disputed land titles. His cowboys also needed trail gear and several horses, called cow ponies. About six ponies per man was the usual demand. The cowboys also wanted the amusement and entertainment supplied by the town saloons before they began the long, long arduous months of cattle driving. Oakville is purported to have had seven saloons at one time, but that could not be documented. However, the many tales of drunken carousing by the cattle crews indicates that a lot of liquor was sold somewhere to someone, and, afterwards, the jail was the place to sober up.

By 1890, ranching alone had reached its potential, both in Live Oak County and in Texas. From then on the county's population growth was from other sources and for some decades, it was from farming. As the area west of the Nueces River was reclaimed from the outlaws and was fenced, it became the site for more farming and the population center of Live Oak County moved west and away from Oakville. By the 1880s, dry farming was tried and failed regularly in the county. It was caused by the irregular but cyclical droughts of South Texas. But driven by the "boosterism" of the 1880s and 1890s, new settlers came in regularly to replace the failed farmers who had arrived just a few years earlier. This caused a cyclical prosperity for each town that was, in turn, jealously coveted by the other small towns of the county. Thus, competition among towns for the county seat was mostly for the commerce it always attracted. County seat wars are legendary in Texas because the social, legal and commercial activities that the courthouses attracted. Possession of new courthouses and jails was more apt to make the town more prosperous and attractive than other towns.

The construction of a new, state of the art jail was literally an advertisement to incoming settlers that this town would last and that it promoted civility and safety for its community members The jail 's construction and presence gave the town a sense of substance and provided, however temporal, a pride about the assumed greater prosperity of town life as compared to the less prosperous life of farming or ranching.

Oakville was a microcosm of its booming neighbor to the north, San Antonio, which in the 1880s also went through a heady decade of growth. By the 1880s Oakville not only shipped cattle, horses, cotton and wool, but also listed a dozen stores, two hotels, a livery stable, steam gristmill, school and two churches.

In 1913 prominent rancher George West persuaded the San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf Railroad, affectionately called the "Sausage" line, to place its track through his new town of George West in 1913. When West pledged money to build a new courthouse and jail, Oakville's decline was assured. West, always the entrepreneur, wanted to develop his property instead of ranching it and recognized that the railroad was the path to the future, not the county's rutted wagon roads. In 1919, the county voters elected to relocate their county seat to George West. The railroad bypass of Oakville was the beginning of its decline and the subsequent removal of the county seat only accelerated it. Ultimately the jail also represented the frailty of town prosperity. Oakville would become a ghost town, with only the stubborn stone jail to mark its passing. Town abandonment happened not only because of poor crops and dry climate but also because of technology and politics.

Significance of the Property as Related to the Law

Reduction of Lawlessness in Texas

The Civil War had left behind much unrest in Texas, and some of this spilled over into frontier violence in the form of horse thievery, cattle rustling, carousing and drunkenness. In the 19th century, penal codes tended to grow in bulk and also reflect businesses' sensitivities toward crimes against property. In Texas, besides the general rules for theft and larceny, Article 746 aimed at anyone who stole "any horse, ass or mule." If convicted of stealing the above, one could receive between five and fifteen years in the penitentiary. Cattle rustling was less serious but could be punished with two to five years in prison, and theft of "sheep, hogs or goats" all depended on their value, earning a fine or a year in the county jail.

Prior to the 1880s, the land between the Nueces and Rio Grande Rivers, part of which was in Live Oak County, was sparsely settled by unfenced ranches. Sometimes the Nueces River, not the Rio Grande, was regarded by

Mexico as the true boundary between itself and the United States. The area was subject to frequent Indian raids and to persistent cattle rustling by Mexican entrepreneurs who wanted to sell beef to the prosperous Cuban market.

Like the judge's regular schedule of hearings, the Oakville Jail of the 1880s symbolized the tardy but ultimately orderly arrival of the law to Oakville and to frontier Texas, due both to the work of the Texas Rangers in calming the cattle rustling and border wars with Mexico, and to the more orderly fencing of the open range with Glidden's barbed wire invented in 1873. Fence cutting became such a serious crime that in 1883, the Texas

Legislature passed a law making it a felony.

Murder and rape of townspeople were not frequent crimes. Lawrence M. Friedman, author of Crime and Punishment in American History, states that there was violence in the west, but only in a "special way." There

were plenty of shoot-outs but not much robbery or rape. The violence was "men fighting men" in fistfights or gunfights. But Friedman aside, taciturn, longtime Oakville resident Will Wright, interviewed by author David Robinson in A Little Corner of Texas, believed that the earlier "overstated" violence of Oakville, prior to the 1880s, was actually "understated." The only "lurid" newspaper account that was easily found was a relatively late story in the history of the jail. In 1914, the Live Oak County Leader reported that Ysidor Gonzales and Trevino Sanches were convicted of the murder of jail keeper, Harry Hinton, inside the Oakville Jail.

While the fencing of the frontier transformed cattle barons into more peaceful stockmen, it also encouraged a new economy in Live Oak County and Texas of dry farming over ranching. Farming and fencing made Oakville less

violent. Described in an earlier time by historian Walter Prescott Webb as "a hard country where civil authorities were helpless and took no notice of any outrage," it grew into a thriving town of over 400 people.

Architectural Significance of the Property

Jail Design for Safety and Compliance with the Law

The Oakville Jail was the third and the most sophisticated jail facility to be constructed by the Commissioner's Court. Live Oak County was not a rich county, but it was able to build this jail because Texas law had mandated counties to build safe and proper jails and then provided the means, in the 1880s, to fund construction through the sale of bonds backed by the State.

Live Oak County, like so many other Texas counties, built its first two jails with heavy logs, both attached to the courthouse. Often called calabooses (after the Spanish slang word for jail: calabozo), these wooden jails were quickly erected and were relatively inexpensive. A survey of the thirty-six National Register listings in Texas of the courthouses with jails attached to them, plus the stand-alone jails, shows that counties nearly always built log jails first and then, financing permitting, stone structures.

Log cabin jails were not physically healthy or safe for prisoners. In 1873, Governor E. J. Davis, in disgust, disclosed the problems of building substantial jails that were capable of keeping prisoners in and the public out. He stated, "Our county jails are properly attracting public attention. Our jails are as bad as they can be and so not made secure and this is the case in about four-fifths of the counties, the constant escape of the prisoners is made the excuse for the wholesale murder of persons charged with offenses."

By 1876, the Texas Legislature mandated that counties must build and maintain safe and suitable jails. But protection of prisoners was still such a problem that the legislature had to write a separate statute in 1881, to define the word, "safe," as in a "safe jail.” In 1885, the 19th Legislature amended the legislation that had allowed counties to sell bonds for courthouse construction so that counties like Live Oak could use them for jail construction and meet their county obligation with style. In 1886, the county held an election that approved and permitted the Commissioner's Court to sell bonds for $8500 to build a new jail. The Court had seized on the newly available opportunity to enhance the county seat and the image of the town with a substantial new stone jail.

Live Oak County reflected a statewide trend beginning around 1880 when many of the most up-to -date stone jails were built. The primary concern of these jails was humane detention and protection using the latest techniques of construction. These jails were always at least two stories tall, even if attached to the courthouse. Typically, the first floor was designed to contain the sheriff’s offices and living quarters, plus a kitchen to prepare food for the prisoners. The second, and even third floor, in some cases, was always used to house the prisoners. Large but barred windows let in air and light. Inside were the stand-alone cells, made of strap metal bars. To bear the weight of the steel cells, the floors used I-beams from which were sprung long metal supports formed in a semi-circle shape. Also located on the second floor, apart from the regular cells, was at least one, completely separate cell that was used to house juveniles or women, as needed. Separating jail populations by sex or age was an enlightened concept beginning in the 1870s.

As a place of brief incarceration, the jail safely held accused prisoners until trial. Before these second story designs, prisoners could be shot at from the outside or kidnapped for lynching. Typical crimes of the times were horse thievery, cattle rustling, drunkenness, carousing, and fence cutting. All these crimes and particularly that of horse thievery aroused anger in the ranching and farming community. In past times, the accused had not always been safe from vigilante action. If a jail became overcrowded, the extra prisoners were sent to other county jails. Oakville could house five prisoners.

Until 1846, when a central state penitentiary was established in Texas, local jails housed convicted felons. Huntsville Prison commenced and other properties were slowly added to the system. By 1890, the Texas prison population was approximately 3200.

Architecturally Unique in Texas: The Diebold Jail

Fourteen freestanding, nineteenth century jails in Texas are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The Pauly Jail Company of St. Louis built eight of these jails. Only two of the fourteen listings are Diebold Jails, one for Mills County, and one for San Jacinto County. Diebold's major competition in jail construction was the Pauly Jail Company, which built many more jails for Texas counties than Diebold, making the Oakville Jail even more rare. A survey shows that Diebold built only eight jails in Texas. Texas has two hundred and fifty-four counties and all of them had to build jails; many of them were built in the late l9th century using the special jail bonds. Only Live Oak County and Mills County have jails with this unique configuration.

In 1886, the Live Oak County Commissioner's Court contracted with Lucius T. Noyes, the sole representative in Texas of Diebold Lock and Bolt Company of Ohio, to supervise the construction of the new jail. The

Oakville Jail is nearly an exact duplicate of Mills County, which Mr. Noyes was concurrently constructing for it, on behalf of Diebold. Both jails appear to be a "kit" using "plan S-4 7." Both jails appear to be rare because their building configuration is unique to just the two jails. Both use a simple rectangular shape, like many jails, but with these two, the main door is at the front corner of the structure and the prisoner's door is at the rear and opposite corner. The only substantial difference is that the Mills County also employed an architect, along with Mr. Noyes, who used limestone block instead of Live Oak's local sandstone as well as a relatively more delicate metal cornice. Oakville's jail looks more vernacular in comparison. But otherwise the arrangement of windows, rooms, stairs and doors are the same. The Live Oak County Jail is a rare and interesting style of jail. When it was built, it was at the forefront of contemporary jail design, using new architecture to protect both the public and the prisoners. Live Oak and Mills County jails are now the only two examples of Diebold's S-47 jails in Texas.

The Live Oak County Jail is historically and architecturally significant. It reflects Community Planning and Development in the former county seat of Oakville, and remains the only historic building standing in the town.

The jail is significant in reflecting the Law of its time, symbolizing the community's commitment to law and order and meeting higher state codes for jail construction to increase the safety of the public and the prisoners.

The jail is also architecturally significant not only as the only historic structure in Oakville and an intact example of Italianate architecture, but as one of a handful of Diebold Company jails remaining in Texas. me

Live Oak County Jail retains integrity of location, setting, design, materials, workmanship, feeling and association to a high degree.

The jail cells and the remote locking system for Mills County are still intact, dusty and abandoned by the county. The downstairs is used as the Chamber of Commerce for the town of Goldthwaite, Texas.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS AND PAMPHLETS

Adams, Ramon F. The Rampaging Herd; A Bibliography of Books and Pamphlets On Men and Events in the Cattle Industry. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959.

Biggers, Don Hampton; introduction by A.C. Greene; biography by Seymour V. Connor. Buffalo Guns and Barbed Wire : Two Frontier Accounts: A Combined Reissue of Pictures of the Past and History That Will

Never Be Repeated. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, c1991 (originally published 1901).

Cox, James. Historical and Biographical Record of the Cattle Industry and The Cattlemen of Texas and Adjacent Territory. With a New Introduction by J Frank Dobie. New York: Antiquarian Press, 1959.

Dobie, J. Frank. Cow People. Boston: Little Brown, 1964.

______. Straight Texas. Hatboro, PA: Folklore Associates, 1966.

Exhibit on the Historic Jails of Texas. Institute of Texan Cultures, San Antonio, April 1-June 7, 1999.

Kadish, Sanford H., ed. Encyclopedia of Crime and Justice. New York: Free Press, 1983.

Kelton, Elmer. Texas Cattle Barons: Their Families, Land, and Legacy. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 1999.

Fehrenbach, T.R. Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans. New York: American Legacy Press, 1986.

Friedman, Lawrence Meir. Crime and Punishment in American History. New York: BasicBooks, 1993.

Henry, Jay C. Architecture in Texas, 1895-1945. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993.

Lindholm, Thelma. Master's Thesis : The History of Oakville. Texas A & I, 1950.

Live Oak County Centennial. May 2-5, 1956. Commemoration booklet of the Live Oak County's centennial celebration.

Live Oak County Courthouse Records, Case 1051, District Court Docket, Vol.4, p . 104, May 27, 1904 . First legal hanging in the county?

Live Oak County Courthouse deeds, plats, and Commissioner's Court minutes regarding jail construction.

Live Oak County Leader. Weekly newspaper on microfilm while published in Oakville, for three months in 1913. The Center for American History, Texas Newspaper Collection, Barker Collection University of Texas in Austin.

Patterson, P.E. “Test Excavations Along Interstate 37 at Oakville: Live Oak County, Texas.” Texas State Department of Highways and Public Transportation, Report #35 Antiquities Permit #227. Austin: TxDOT,

1987.

Raine, William Macleod. Famous Sheriffs and Western Outlaws. New York: New Home Library, 1944.

Robinson, David. A Little Corner of Texas. Tulsa: John Hadden Publishers, 1991.

Robinson, Willard Bethurem. The People's Architecture: Texas Courthouses, Jails, and Municipal Buildings. Austin : UT Austin Press in cooperation with THC, 1983.

_ _____. Texas Public Buildings of the Nineteenth Century. Austin: University of Texas Press for the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art, 1974.

Roth, Mitchel P. Crime and Punishment: A History of the Criminal Justice System. Houston: Sam Houston State University, due out November 2002.

Sasser, Elizabeth Skidmore. Dugout to Deco: Building in West Texas, 1880-1930. Lubbock, Texas Tech University Press, 1993.

Siringo, Charles. A Texas Cow Boy or Fifteen Years on the Hurricane Deck of a Spanish Pony (1885). The Center for American History , The University of Texas at Austin.

Sparkman, E. L. The People's History of Live Oak County, Texas. Mesquite, Texas: Ide House Publishers, 1981.

St. Clair, K.E . Little Towns of Texas. Jacksonville, Texas: Jayroe Graphics Arts, Inc, 1982.

Webb, Walter Prescott. The Great Frontier. Austin : University of Texas Press, 1964.

_ ___ __. The Story of the Texas Rangers. New York: Grosett, 1957.

Wellman, Paul I. A Dynasty of Western Outlaws. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

WEB SITES

Diebold Co. Canton, Ohio, homepage. (Company supplying jail cells for Oakville Jail.)

Information on L.T. Noyes, agent for Diebold in Texas. www.rootsweb.com

Texas Historical Commission. thc.state.tx.us (Landmark Atlas to find other jails designed by Diebold Co. or architecturally similar jails such as the Mills County Jailhouse.)

Texas State Library and Archives Web Site, www.tsl.state (General highway map, Live Oak County, Texas, 1940).

The Handbook of Texas Online, www.tsha.utexas.edu

Pauley Jail Co., St. Louis, home page (Diebold's competition).

Sanborn Maps on the Internet. Sanborn for Goldthwaite, Texas, shows courthouse and jail location just like Oakville's main square configuration.

ORAL HISTORIES

Mr. Roy Jones , -Oakville Jail property owner.

Mr. Jim Harrod, adjacent property owner and longtime resident of Oakville.

Ms. Etienne Harrod, long time Oakville resident and librarian for the Live Oak County Library.

HELPFUL PLACES

Armantrout Museum, (town of) George West, Texas

Live Oak County Courthouse, George West, Texas (minutes of Commissioner's Court meetings, and many recorded documents).

Live Oak County Tax Assessor/Collector, George West, Texas (ownership records of Oakville Main Square).

Oakville Baptist Church, Oakville , Texas (Church history).

PHOTOGRAPHIC INVENTORY

Live Oak County Jail

Public square (Block 7)

Oakville, Live Oak•County, Texas

Photographs by Bob Brinkman, March 2002.

Negatives on file at Texas Historical Commission.

Photograph 1 of 4

South elevation

Camera facing north

Photograph 2 of 4

West elevation

Camera facing east

Photograph 3 of 4

South elevation window detail

Camera facing north

Photograph 4 of 4

South elevation stone detail

Camera facing north

OMS Approval No. 1024-0018

Live Oak County Jail

Oakville, Live Oak County, Texas