D Surnames

Dungan letter of Oakville Nostalgia "Oakville circa 1892" The People's History of Live Oak County, Texas. 1981, Ide House. Mesquite. 90-93. Ervin L. Sparkman, Author Irvine Dungan, Letter Author

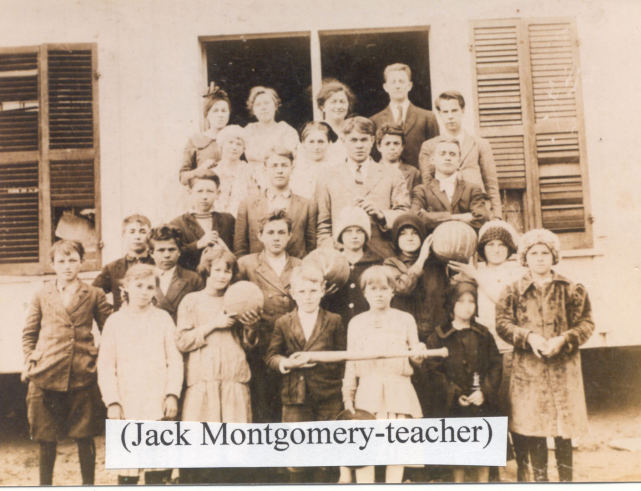

Oakville Nostalgia by Irvine Dungan, Oakville Teacher 1892-93

Old Oakville Nostalgia

Over the course of its first fifty years, Oakville and its people produced amazing stories of endurance and fortitude. Stories of the Civil War, cowboys, gunslingers, banditos, desperados, Indian depredations, and Texas Rangers birthed its Wild West image.

But there is a gentler, nobler side to Oakville that becomes lost in those frenzied stories of old. Below are excerpts from a letter sent to the Live Oak Herald in 1941 and later recorded in Ervin Sparkman’s The People’s History of Live Oak County, Texas pages 90-93.

The letter writer, Irvine Dungan, was a teacher from Ohio who instructed children in the Oakville School between 1892 and 93, about five years after the last Oakville Jailhouse was built. Here’s what Dungan had to say:

“Lately, I have been having homesickness for Oakville, and to see some of the boys and girls who went to school to me. I had those [students] from about twelve to eighteen in age; and the younger ones were taught by Miss Patty Reagan, fine and capable.

My oldest pupils were three brothers, Willie Lyne and the twins, Reuben and Rufus. I often think of them and the big box of hides they sent me, of Mexican leopard, bob-cats, deer and wild hog that they had shot, which gave me some attractive rugs.

I recall Bert McBride, and a pet raccoon which he brought to school one day. I told the youngsters that we would let Bert keep the little fellow inside, leashed to the desk, for safety if we all would not let it distract our attention from our work. It was too far for Bert to take the pet back at once. He and his sister came three or four miles to school in a cart.

I remember Eugene Nation, a keen, fine looking lad; and Green Cude, a bit lanky, and the Wheelis boys, Green, Sam, Ira, and Dillard. Sam would be out of school for a few days now and then to break a pony. Some of the girls in school were Mamie Gilmore, and Tidy, daughters of Captain Gilmore, who was on the school board, also the daughter of Mr. Atkins, the editor [of The Live Oak County Leader]; Flora Wright; Nellie Wimmer, and Fay Hatfield.

Out of school, I remember Dr. Orr and his drug store; Otto Wimmer and his big general store; Mr. Hatfield, blacksmith and teacher of the Methodist Men’s Class, which I attended; Eugene Reagan, of a sterling manliness, Miss Patty’s brother, who had lately brought down from Kentucky a car-load of horses, with [an African-American. Dungan used the politically correct term at the time “Negro”.] who got a job at the Chester House, and whom I taught to read and write a little, so he could read his mother’s letters and answer them. (And Jim used to ring the first bell for breakfast, then come and stick his head in my door and say, ‘P’fessor, I’ve got de cream at your end of the table.’)

I used to enjoy going to Judge Cox’s office in the court house for little chats with him—C.C. Cox, born in my state of Ohio, next a boy in Tennessee, then to Texas where he was in the navy of independent Texas, later in the Confederate Navy. Captain Gilmore, a Confederate Cavalry officer, was an encouraging friend, and a most interesting narrator of experiences of a cultured and splendid man.

I recall Squire Chester, of course, a Connecticut Yankee who became a Texas Justice of the Peace, and proprietor of the Chester House where I lived in Oakville.

In the Chester House, in a September court week, one of the visiting lawyers shared my room—General Bagby, a Confederate brigadier general who told me many interesting things about his West Point days, and his visits to Washington where his father was a U.S. Senator from Alabama, and where he got to see and hear men like Calhoun, Clay, and Webster.

General Bagby told me he had never taken the oath of allegiance after the war, to be able to vote, but he had a good friend and client who was in a hot race for sheriff, ‘and he is insisting on my taking the oath so I can vote for him, and I reckon I’ll do it.’

Templeton kept a hotel near the Chester House, who as a boy of about fifteen had been a guard in the Confederate prison stockade at Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas at a certain time in the war—which happened to be part of the time that my father and his Nineteenth Iowa regiment were prisoners there, captured in a fight near Morgan’s Bend, Louisiana.

I would rather hear that Oakville orchestra now than any other music I know. There was Paul Bauer and his flute, Herman Wimmer and his banjo, George Orrick with his harmonica, and a blind man, Eddie Lyons with his violin.

My favorite loafing place was Paul Bauer’s shop, and (was) secretary of the school board, also chairman of the Democratic county committee. When Congressman Crain came to town for a meeting, (my father and Mr. Crain being friends in Washington) Mr. Bauer got a pint of whiskey and gave it to me to slip quietly to Mr. Crain at the hotel, so there would be no need to go to the saloon; I surreptitiously eased the package to Mr. Crain, who passed it around to the half-dozen or more men in his hotel room before he took a drink himself. Interesting group and interesting speech at the court house afterwards. Mr. Crain was a man of eloquence and personal charm.

Paul Bauer shaped for me an 18-inch leather strap for emergency use at school, saying, ‘switches don’t keep.’ I had to use the strap only two or three times.

George Orrick and Herman Wimmer were mighty good pals—horseback rides, music, lemonade made with cold water from a well back of the store, sugar from the Wimmer store and lemon extract and tartaric acid from the drug store, lemons and ice being at that time unobtainable in Oakville except as ‘special’.

. . . I can help out my recollections and my homesickness, by getting the Oakville paper for awhile anyhow and maybe seeing an occasional familiar name.

If any of those youngsters of mine are still in the old town, and might feel kindly like treating this as a letter to them, and would answer it, and tell about “who’s who up to now, I would surely appreciate it.

Very truly yours,

Irvine L. Dungan"

Well, the editor of the Live Oak County Herald, the Bee-Picayune or Mr. Sparkman definitely cut some of the letter. We can only imagine what was left out. Thanks, Mr. Dungan, for this small window into Oakville’s past.